Nuclear DNA From Neanderthals Recovered From Sediments For Very First Time

A team of researchers has managed to recover nuclear DNA from several Neanderthal individuals without fossilised remains by investigating the sediment at three prehistoric caves.

This potentially opens a new door for future investigations and even in theory for the cloning of Neanderthals, as bones or other remains will no longer be required to know more about cave-dwelling populations.

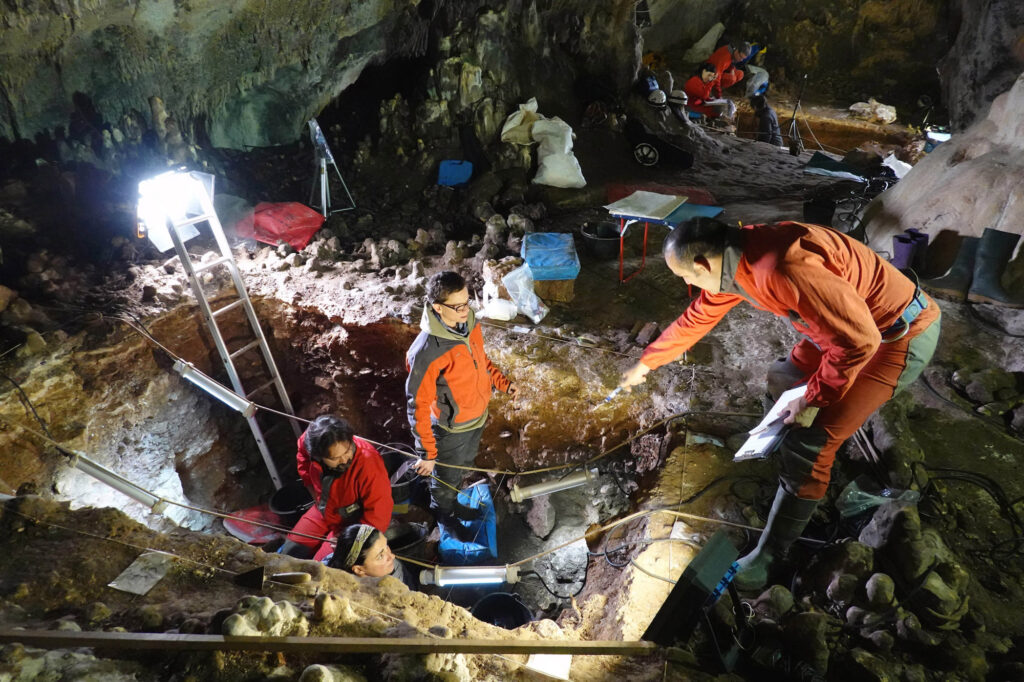

The nuclear DNA was recovered from the sediment at two Siberian caves – Denisova and Chagyrskaya – and the Galeria de Estatuas (Statues Gallery), located in the Cueva Mayor (Main Cave) at the Atapuerca Archaeological Site in the northern Spanish province of Burgos.

The research, recently published in ‘Science’ magazine, was led by Benjamin Vernot of the Max Planck Institute of Anthropology in Germany.

According to the researchers, “human fossil remains will not be needed to identify the population living in a prehistoric cave”.

The excavations carried out at the Galeria de las Estatuas led by Juan Luis Arsuaga, scientific director of the Museum of Human Evolution, took place in 2008.

Remains of animals taken by the Neanderthals were recovered at the site, as well as tools from between 115,000 and 70,000 years ago and the phalanges from a foot dating back 110,000 years.

This cave is unique, as it is totally isolated, and the sediments have remained unchanged thanks to the humidity and temperature conditions and they have not suffered any alterations from natural causes or modern human interventions.

Previous research projects had managed to collect mitochondrial DNA from the sediments, but this is the first time it has happened with nuclear DNA.

Mitochondrial DNA from sediments is not enough to fully identify the population living in a cave because even though it is more abundant and easier and cheaper to collect, it only gives genetic information about the maternal lineage.

On the other hand, nuclear DNA contains much more genetic information (around 3,200 million base pairs in comparison with the 16,000 base pairs from mitochondrial DNA), but it is more difficult to preserve.

Therefore, it is difficult to encounter, and it needs to be under special temperature and humidity conditions like the ones in the Galeria de las Estatuas. It also contains genetic information about both paternal and maternal lineages.

Thanks to the information gathered from the nuclear DNA, the researchers have found out that there were two different lineages at the Galeria de las Estatuas.

Eudald Carbonell, professor of prehistory at the Rovira i Virigili University, co-director of the excavations at the Atapuerca Archaeological Site, and one of the authors of the research, explained to Real Press that “there were two waves of Neanderthals occupying the cave” thanks to the nuclear DNA analysis, which “is amazing” to know.

The phalanges found in the cave belong to the first lineage living there. The DNA of the oldest individual belonged to a Neanderthal man dated back around 110,000 years, although his lineage originated before, around 130,000 years ago.

The date calculated for that “radiation”, the name for when lines from a common ancestor separate, is close to the beginning of the last warm period between two glaciations.

From this, scientists concluded that it is possible that there might be some relationship between the environmental and ecological changes at that moment in history that could have affected the evolution of old human beings.

The second piece of nuclear DNA is dated back around 80,000 years, and the researchers identified genetic remains of at least four women. The climate had changed by that time, as the last glaciation had started.

The Neanderthals from the last glaciation are commonly known as “classic” and are more studied, with more exaggerated characteristics.

One of the most important unique characteristics is that they had the biggest brains of the whole human evolutionary line, even bigger than ours.

These findings show that in Atapuerca, there was a replacement of the Neanderthal population around 100,000 years ago, a change that was probably a consequence of a change in climatic and environmental conditions, according to the researchers.

Carbonell said that despite this information, it is unclear how many generations both lineages had.

In the Siberian cave of Chagyrskaya, research confirmed that the site was always occupied by the same Neanderthal population.

The Galeria de las Estatuas is the lesser known of the caves at the popular archaeological site. The name comes from the huge stalagmites created there over one million years ago.

The cave was open in Neanderthal times, but when Homo Sapiens arrived in Atapuerca, they could not enter the cave, so only Neanderthals lived there.

However, Carbonell explained that “the cave was used by those populations, hunters and collectors, as a shelter from weather conditions, as they commonly lived outside, but the caves were always used for protection”.

The coordinator of the Atapuerca project told Real Press that “the Neanderthals were a complex population, very evolved for their time, with their own language”.

According to the researcher, being able to take nuclear DNA from sediments opens a new door for investigations, as fossil remains will no longer be needed to know more about a population.

Speaking about the fact that the latest development meant obtaining DNA from the ground without actually having fossilised remains Carbonell said: “Genetic enginery has made a fundamental leap in the last few years; we all human beings have 40 percent of the genome of Neanderthals.

“With technology, we could even eventually fabricate a Neanderthal, but the question would be what for?

“For the human race, science has no limits, the limit is the imagination, and then the capacity for making it true.”

“Once science opens a hole, the human capacity to exploit it is infinite.”