Shipwreck That Led To First European Settlers In Australia Reveals Seafaring Domination Secrets

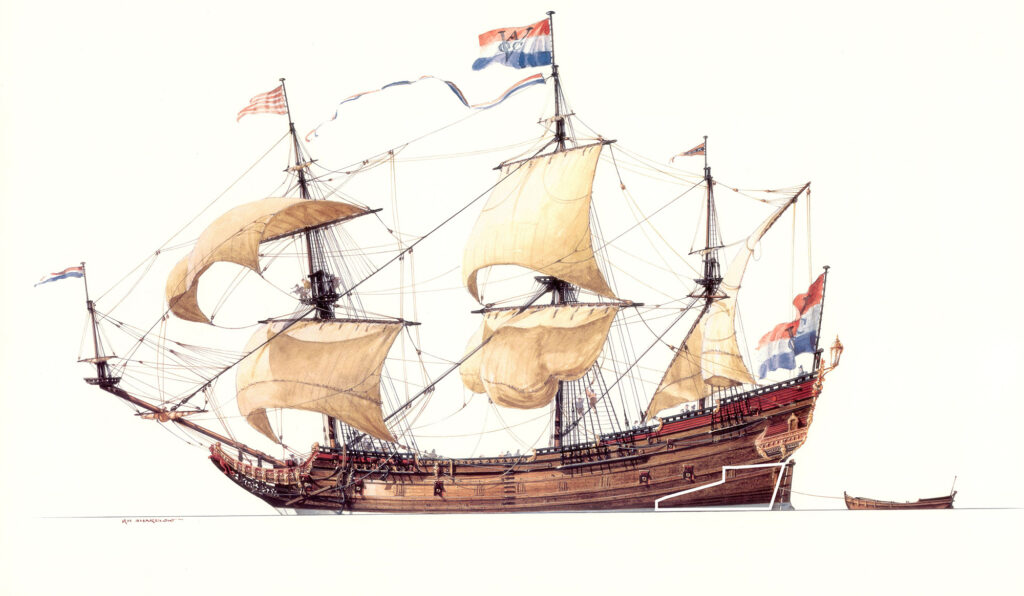

A study into the timber used to build the Batavia ship that ended up sinking off the coast of West Australia in the 17th century resulting in the first official European settlers has revealed how the Dutch republic’s trade network allowed it to overcome timber shortages that plagued other nations.

Researchers have now studied the timber used to build the ship between 1626 and 1628 in Amsterdam to reveal how Dutch shipbuilding techniques allowed the Dutch East India Company (VOC) to flourish against other European powers such as Portugal and France.

Marta Dominguez Delmas, Research Associate and VENI Fellow at the University of Amsterdam, told Newsflash: “The VOC used exclusively oak (Quercus sp.) for the main structural elements (hull planks, framing elements, keel, etc), with Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) used for sacrificial planking (in the outer part of the hull, below the waterline).”

Marta added that the Dutch were able to avoid timber shortages because they had an extensive trade network delivering wood from northern Europe.

The British took great pride in building their ships with ‘locally sourced’ oak whilst the Spanish and Portuguese became dependent on the Dutch Republic to supply them with timber.

Delmas said: “The Dutch were actually the ones supplying timber, from Scandinavia and the Baltic to Spain and Portugal.”

According to a statement released by the University of Amsterdam yesterday, 1st November, Although 706 ships were built on the VOC shipyards in the Dutch Republic, very little is known about the timber itself, where it was sourced from and how it was used to build the ocean-going vessels.

Wendy van Duivenvoorde, Associate Professor at Flinders University and leader of the study, said that despite the Dutch Republic’s lack of domestic sources during the mid-17th century, it was able to produce unprecedented numbers of ocean-going ships for long-distance voyaging.

By studying the Batavia wreck, Duivenvoorde and her colleagues from the University of Amsterdam and Copenhagen were able to shine a light on the history behind the VOC’s success.

Delmas explained that the ship named ‘Batavia’ was headed for a city by the same name which was the capital of the Dutch East Indies known today as Jakarta, Indonesia.

She added: “The Batavia ship sailed too far east and when it made the turn north it ended up wrecking on the reefs of Abrolhos Archipelago, off the coast of Western Australia.”

The Batavia sank off the coast of a string of small islands and out of 341 passengers on board, 40 drowned while the rest swam ashore.

The ship’s commander, Francisco Pelsaert, left his crew to return to Batavia, which was the capital of the Dutch East Indies located in modern-day Indonesia.

Jeronimus Cornelisz, a merchant, was left in charge and after sending 20 men to look for water on a distant island, he orchestrated a mutiny that resulted in the death of 125 crew members and he turned the female survivors into sex slaves.

The 20 men returned and found out about the atrocities committed by their leader and organised a revolt.

Francisco Pelsaert returned to the small chain of islands, off what is now the western Australian coast, as the fighting raged and had Cornelisz and his co-conspirators tried and convicted.

Six of the mutineers became the first European men to be legally executed in Australia and two of the men were exiled to the continent becoming its first official European settlers.

The Batavia was raised from the seabed in 1970 and has since been on display at the Western Australian Shipwrecks Museum in Fremantle.

The researchers took samples from the ship’s hull timber and analysed them to get a better understanding of the materials used to construct the mighty 650-tonne ship.

Delmas said: “Oak was the preferred material for shipbuilding in northern and western Europe, and maritime nations struggled to ensure sufficient supplies to meet their needs and sustain their ever-growing fleets.”

She added: “Our results demonstrate that the VOC successfully coped with timber shortages in the early 17th century through diversification of timber sources.”

Van Duivenvoorde concluded by saying that the Dutch Republic in the 17th century was supplied with a wide range of timber from different regions allowing it to overcome shortages that would have held back its shipbuilding ambitions.

The study was published under the title ‘Batavia shipwreck timbers reveal a key to Dutch success in 17th-century world trade’ in the journal Plos One on 29th October.