German Researcher Manages To Make Coral Mate In Lab

A German researcher has managed to make coral mate and reproduce in a laboratory using a complicated simulation right down to making sure that everything from water temperature through to the moon cycle were exactly the same as in the wild.

Professor Dr Peter Schupp and his team of scientists from the Institute of Chemistry and Biology of the Marine Environment of the Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg carried out the project in aquariums at the Wilhelmshaven site in Lower Saxony.

Researchers simulated the environmental conditions in the laboratory to correspond with the Pacific Ocean.

The classification of corals has been discussed for millennia due to them having similarities to both plants and animals.

However, they were considered plants until the 18th Century when scientist William Herschel used a microscope to establish that coral had the characteristic thin cell membranes of an animal.

Dr Samuel Nietzer, who runs the Wilhelmshaven Aquarium, told Newsflash: “This is a big step for coral research in Germany.”

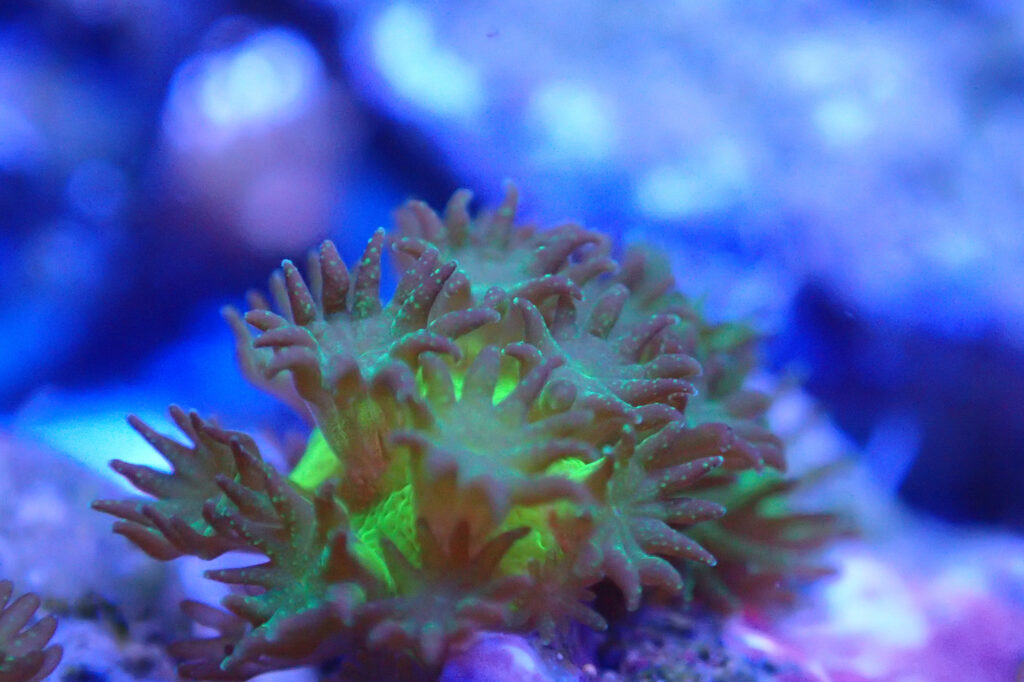

The evaluated species, Acropora tenuis, can be found in tropical shallow reefs on upper slopes and in sub-tidal habitats at depths of 8 to 20 metres (26 to 66 feet), however, these genetically identical corals are extremely vulnerable to environmental changes such as rising water temperatures.

Experts now hope that sexual reproduction can help future generations become more resilient and adapt better to altered conditions.

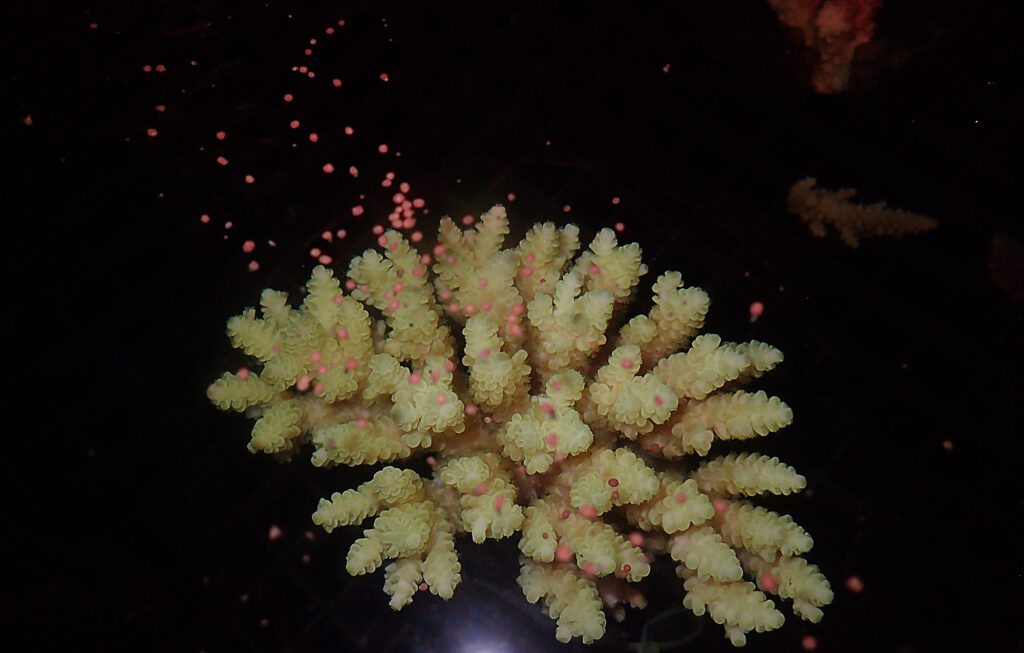

To spawn Acropora corals, scientists implemented a special technology in the Wilhelmshaven aquariums to create a suitable environment for corals which originated from Australia.

Furthermore, water chemistry lunar cycles and parameters such as length of day, light and temperature were artificially simulated.

Nietzer added: “We simulate their home climate with special computer programmes. With the Australian corals for example, the sun sets at noon and rises at midnight.”

A week after the full moon in December, corals released eggs and semen into the water.

The scientists then mixed eggs and semen from different colonies to achieve genetic diversity.

Nietzer said: “We achieved a fertilisation rate of almost 100 percent and a few days after we got 50,000 developed larvae.”

He also mentioned that the largest offspring to survive is now one centimetre tall.

Schupp explained the importance of identifying factors that promote coral settlement and growth and emphasised that environmental influences such as marine pollution should also be taken into consideration.

He added: “We assume that new findings and methods of rearing will result in large quantities of young corals being grown in the future and that the methods developed in the process can be used, for example with damaged reefs and in coral research.

“We hope to be able to contribute to the preservation of this unique and valuable ecosystem with studies focused on larvae settlement and young coral growth.”

In addition, the working group of 16 scientists is also investigating anti-cancer and anti-viral effects of chemical ingredients from sponges, sea cucumbers and corals.

Schupp told the newspaper Bild: “There are already seven approved drugs worldwide that are made from the chemical substances of marine organisms and many more are already in clinical trials on humans.”