SQUID GAMES: Austrian Scientists Find Worlds First Proof Of Fossilised Squid Cartilage Using Home Office To Work In

A team of experts and science enthusiasts led by a married couple of palaeontologists who managed to keep working by turning their home into a science lab have discovered the world’s first evidence of fossilised squid cartilage from a site in provincial Austria.

Researchers at Vienna’s Natural History Museum (NHM) and the University of Vienna have examined over 10,000 unique fossils from the Alpine Triassic period, an era dating back approximately 233 million years.

The fossils all came from a small trench not far from the Polzberg Mountain, a popular hiking area near the town of Lunz am See in the State of Lower Austria, around 140 kilometres (87 miles) from the federal capital Vienna.

Experts underlined that the Polzberg area has been one of the most important fossil sites in the country.

During the past 150 years, spectacular discoveries have been made there. Only last year, previously unknown black structures that were carbonised remains measuring up to three centimetres (1.18 inches) were unearthed during excavations conducted by the NHM and members of Oesterreich Forscht (Austrians Are Researching), an initiative organised by the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna, encouraging amateurs interested in science to participate in research.

Now Vienna University palaeontologist Dr. Petra Lukeneder and her husband Dr. Alexander Lukeneder of the NHM have used computer tomography (CT) to examine over 80 different specimens of these fossils and their enigmatic structures.

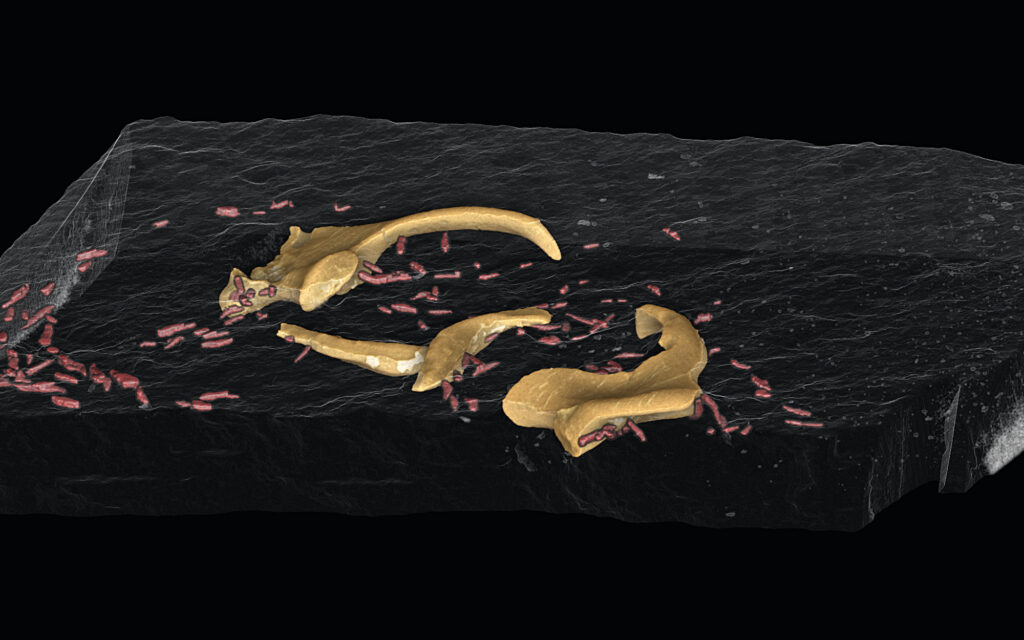

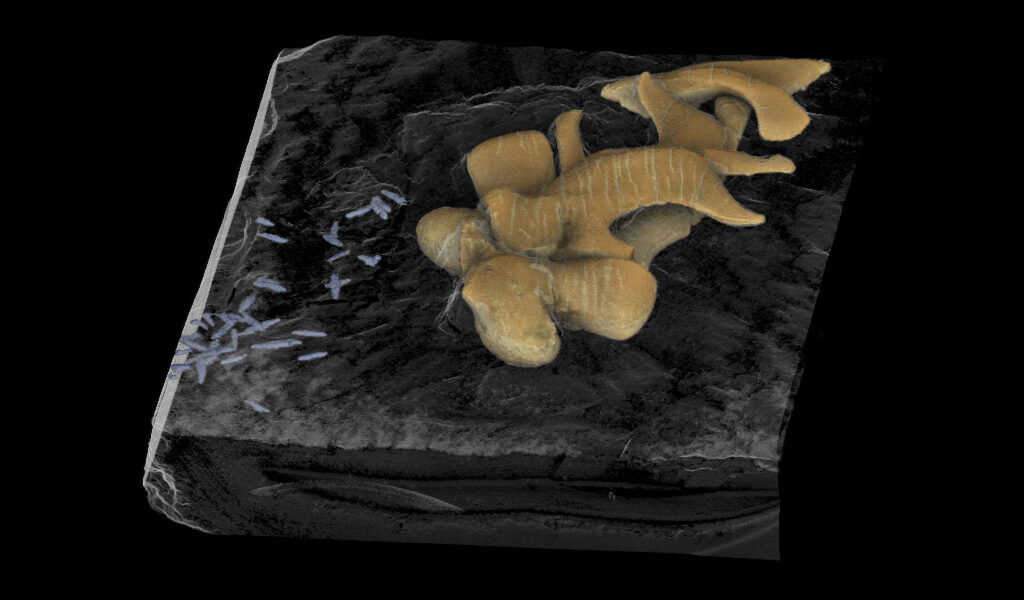

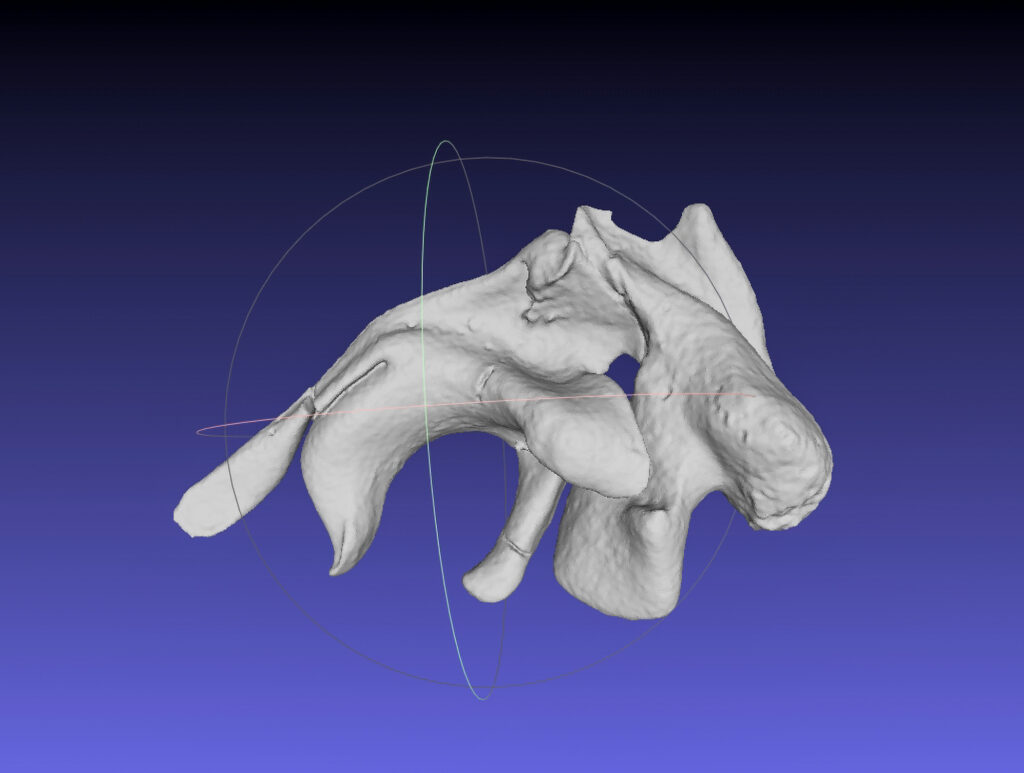

The micro-CT images enabled the researchers to see inside the structures for the first time. The scanner produced image after image of the fossilised remains, allowing them to create digital 3D models, which were crisscrossed by a huge number of ramified passages. In addition, the chemical composition was determined by means of studying ultrathin rock sections under a scanning electron microscope and conducting a high-resolution material analysis.

In the objects, which consist of pure carbon, hundreds of tentacle hooks were found embedded. Cuttlebones, the calcareous shells of these molluscs, were also found near the black structures.

The researchers compared the three-dimensional digital models with modern animal groups, which enabled them for the first time to unequivocally identify these enigmatic finds as fossilised squid cartilage.

Geochemical processes led to a gradual accumulation of carbon in the originally cartilaginous material and resulted in the preservation of these structures which are now blackened and hard.

The finds could be assigned to the cephalopod species Phragmoteuthis bisinuata, which lived 233 million years ago and is an extinct relative of the modern squid. Modern-day squid, such as Loligo vulgaris, the common squid, develop very similar cartilage structures in the head area which strengthens and protects the animals’ brain and eye region.

This phase of Earth’s history saw a worldwide crisis involving mass extinction on the planet that lasted for over two million years.

This crisis also had an impact on the sediments and deposits on the seafloor, leading to the formation of oxygen-poor areas in the lowermost water masses of the ocean. As a result, even the finest details of the fossils were preserved in the hostile mud, making the Polzberg area in Lower Austria a unique site for palaeontological research.

In September 2021, Alexander Lukeneder told national broadcaster ORF how his wife and himself turned their home in Gablitz, a small town with 5,000 inhabitants just outside Vienna, into a laboratory during the COVID-19 pandemic. The scientist explained: “Lockdown and various working place restrictions did not leave us any other option. I do the raw labour, so to say, separating rocks and pebble stones not containing any fossils from those that did. Then my wife took over. She takes a closer look and investigates them further.”

The father of two added: “All of this is taking place in our home office laboratory. We set it up ourselves, we financed it on our own. All scientifically relevant discoveries are registered before becoming part of the collections of the Natural History Museum in Vienna or the Landesmuseum (Museum of the State of Lower Austria) in Sankt Poelten.”

Their latest results have been published in the PLOS ONE scientific journal.