OWLS ABOUT A SNACK? Six-Million-Year-Old Owl Fossil Found Had Its Lunch In Its Stomach

Scientists are expecting to make major advances in discovering how owls evolved after this remarkably well-preserved skeleton of an extinct species that lived more than 6 million years ago was found in China.

The incredibly intact fossil even included the remains of the bird’s last meal, a small mammal that was still being digested in its stomach when it died.

The fossil was discovered at a high altitude of 2,100 metres (6,890 feet) on the Linxia Basin, in Gansu, which is a landlocked province in Northwest China, near the Tibetan plateau.

After studying the well-preserved remains, the researchers from the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences were able to confirm that it dates back 6 million years, to the late Miocene Epoch.

Despite the fact that it is an ancestor to the modern-day owl, the scientific team believes that this particular species was most probably active during the day rather than the night.

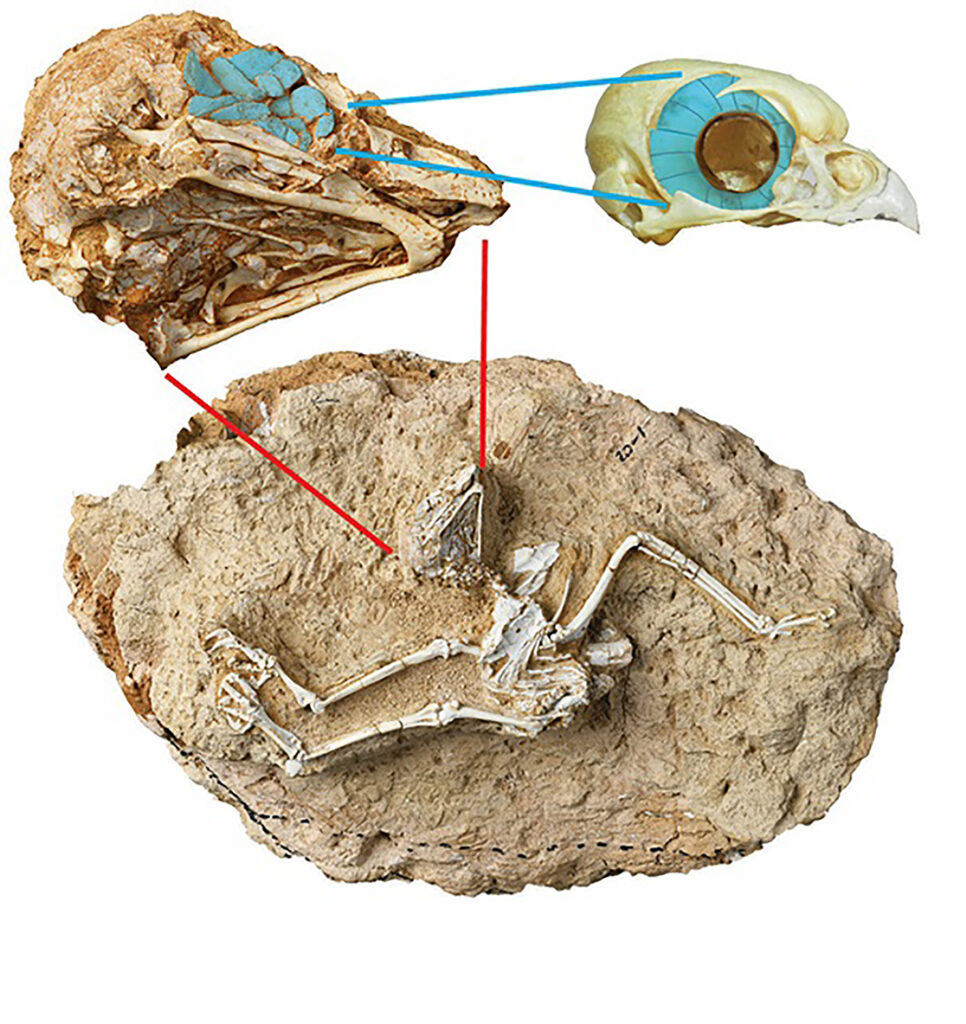

Dr Li Zhiheng, who co-authored the study along with Dr Thomas Stidham, said: “It is the amazing preservation of the bones of the eye in this fossil skull that allows us to see that this owl preferred the day and not the night.”

The scientists are hoping to make significant advances in discovering the way owls developed based on the fossil, which is almost complete, from the skull through to the wings, legs and tail bones.

Other unusual parts not usually found as fossils include the tongue, the trachea and the kneecap, as well as indications of the presence of tendons located in the wing and leg muscles.

The fossil has been given the scientific name Miosurnia diurna in a nod to its closest living relative, the diurnal (active during the day) northern hawk owl (Surnia ulula).

It is believed that the fossil is the first on record showing a prehistoric diurnal owl.

Such creatures would have had small eyes, and scientists were able to construct the size of the prehistoric owls’ long-decayed eyeball by putting the bones that would have surrounded it back together.

The study compared the scleral ossicles of this owl fossil with eyes of 55 reptile species and over 360 bird species, including many species of owls, and proved that the eyes of this extinct owl were less open to light, which suggests that the species was diurnal and did not need effective night vision.

The study was published in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on 28th March.