People In Worlds Oldest City Walled Up The Painted Skeletons Of Their Dead Before Digging Them Up And Passing Them Around

The inhabitants of the “world’s oldest city” – now a UNESCO World Heritage Site – painted the skeletal remains of their dead and buried them in the walls of people’s homes.

They would also dig them up again and pass parts of the skeletons, including their skulls, around the community before walling them up again and redecorating by repainting their walls.

The study was conducted by a team of international researchers led by the University of Bern in Switzerland, with the institution saying in a statement obtained by Newsflash that the research provides “new insights about how the inhabitants of the ‘oldest city in the world’ in Catalhoyuk buried their dead.”

The 9,000-year-old Neolithic proto-city of Catalhoyuk, in what is now south-central Turkey, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site that is about 130,000 square metres (1.4 million square feet) in size and is made up of mud-brick buildings that were built closely together.

The researchers said that some of the settlement’s inhabitants were buried inside the walls of homes and that this was an opportunity to repaint the house, with the remains, including their skulls, sometimes dug up and passed around the community.

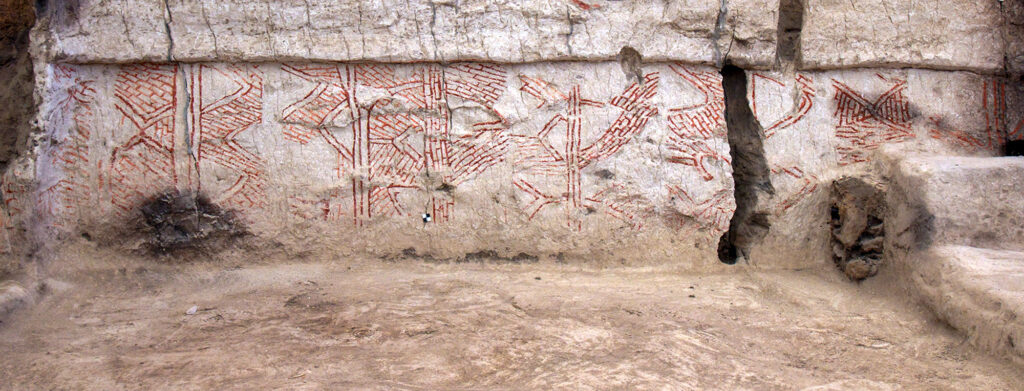

The 9,000-year-old burial ritual included intramural burials with skeletons walled up in the early human dwellings and with the walls being painted a reddish colour using the natural, clay-earth pigment ochre.

The University of Bern said that the study yields “insight into the burial rituals of a fascinating society that lived 9,000 years ago” when deceased people had their bones “partially painted, excavated several times and reburied”.

The university also said that red ochre, which is a natural pigment made up of a mixture of ferric oxide, sand and clay, was “commonly” used at the settlement and that it was found on “some adults of both sexes and children”.

The study’s lead author, Marco Milella, of the Department of Physical Anthropology at the university, said that cinnabar, which is a toxic, mercury-based mineral, was also found on the remains of some of the city’s inhabitants.

A blue-tinted cinnabar paint was found on some of the remains of men, while a green version of the cinnabar was found on some of the remains of women.

The university said in its statement: “Intriguingly, the number of burials in a building appears associated with the number of subsequent layers of architectural paintings. This suggests a contextual association between funerary deposition and application of colorants in the domestic space.”

Milella said: “This means: when they buried someone, they also painted on the walls of the house.”

The statement also said that in “the Near East, the use of pigments in architectural and funerary contexts becomes especially frequent starting from the second half of the 9th and the 8th millennium BC.”

They said that Neolithic archaeological sites in the region have revealed “a large body of evidence of complex, often mysterious, symbolic activities” that included “secondary funerary treatments, retrieval and circulation of skeletal parts, such as skulls, and the use of pigments and architectural spaces and funerary contexts”.

Some of the skeletons “stayed” within the community, with their skeletal remains being retrieved and circulated for some time, before they were buried again. This second burial of skeletal elements was also accompanied by wall paintings.

Milella was part of the team of anthropologists who excavated and studied the human remains. The study said that only some individuals were buried with the ‘paint’ on their bones.

Milella said: “The criteria guiding the selection of these individuals escape our understanding for now, which makes these findings even more interesting. Our study shows that this selection was not related to age or sex.”

But the study reveals that “visual expression, ritual performance and symbolic associations were elements of shared long-term socio-cultural practices in this Neolithic society”.

The findings were published in the academic journal Scientific Reports. The other authors of the study include E. M. J. Schotsmans, G. Busacca, S. C. Lin, M. Vasic, A. M. Lingle, R. Veropoulidou, C. Mazzucato, B. Tibbetts, T. S. Haddow, M. Somel, F. Toksoy-Koeksal, and C. J. Knuesel.