New Super Carnivore Wolf Species Discovered At 1.6-Million-Year-Old Palaeontological Site

Scientists have identified a new species of ‘super carnivore’ wolf from 1.6 million years ago that had more of a meat-based diet than previously known prehistoric wolves.

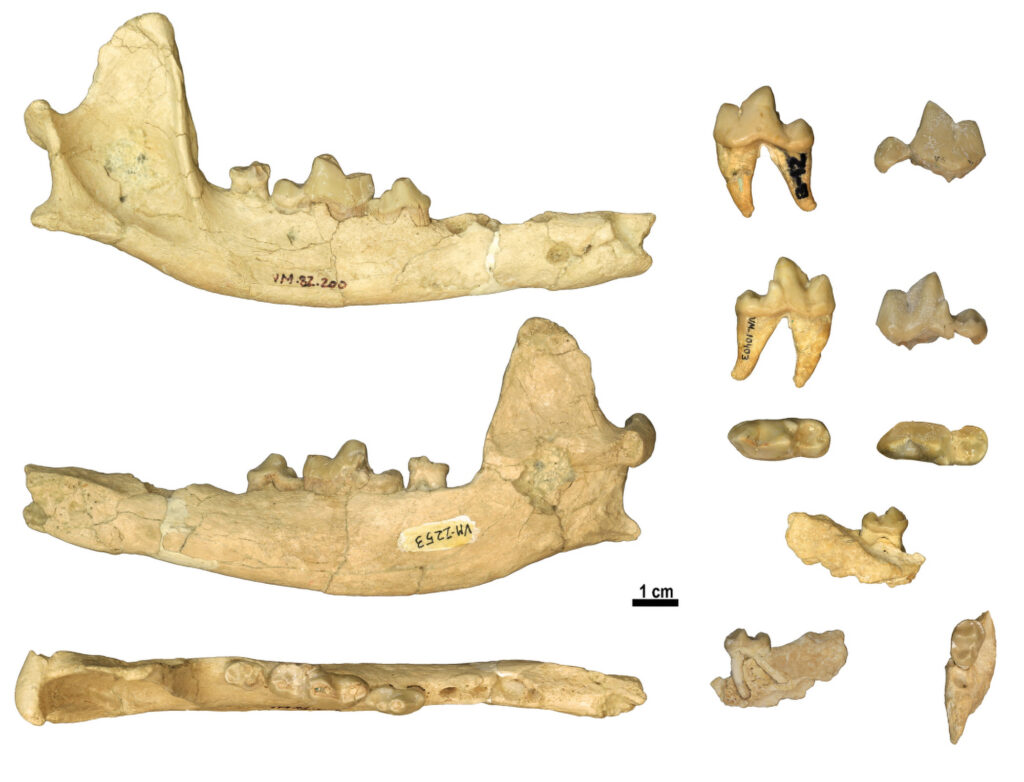

The new species has been named Canis orcensis after the municipality of Orce, in the southern Spanish province of Granada where the fossilised remains were discovered in the Venta Micena palaeontological site.

The site dates back 1.6 million years and has become well-known for containing large mammal fossils from the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs as well as the oldest evidence of human settlement in western Europe dating back between 1.4 and 1.3 million years.

Professor Bienvenido Martinez-Navarro, 57, from the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies explained in an interview with Real Press that the researchers who discovered the new wolf species did so by checking canine teeth found at the site.

The researchers found that one of them was different to all the others belonging to the species Canis etruscus, which was described in Italy in 1877.

Professor Martinez-Navarro said: “The new species identified in Venta Micena is different as its main characteristic is that it has teeth that tend to be super carnivorous. This indicates that the animal ate more meat than other Inferior Pleistocene canines of similar size, whose dietary habits were more omnivorous.”

The professor explained that there previously were three kinds of canines in the Venta Micena site: a big size wolf, which is the ancestor of the current African wild dog (Lycaon pictus), a smaller form of fox, and this new species.

The new wolf species weighed between 15 and 20 kilogrammes (33-44 lbs) and Professor Martinez-Navarro described it as an animal with a long, slender face that hunted for fresh kills as well as carrion.

He added: “It was a wolf similar to current day wolves, but smaller and with a longer face.”

Scientists determined Canis etruscus to be a new species, not just through studying the skull and teeth, but also by geochemical differences such as the abundance of stable isotopes in the fossil that indicated it had a very carnivorous diet.

The professor said its extra-carnivorous habit could be based on the abundance of such prey animals at the time. It co-existed with all kinds of large mammals, he said, and there was an abundance of water in the area, with a huge lake and thermal waters where a lot of fauna gathered.

The site was one of the best water supplies in prehistoric times, which explains the many fossil remain found there, but now the landscape has changed into a desert.

Professor Martinez-Navarro said: “This site is unique in the whole world. It is the biggest with a huge presence of fossil remains.”

He added that it covers an area of one square kilometre (247 acres) and could contain up to 60 fossilised remains in each square metre (1.2 square yards).

The Canis orcensis discovery has been recently published in the magazine, Comptes Rendus Palevol, by Bienvenido Martinez-Navarro and Saverio Bartolini Lucenty, from the Firenze University, Maria Patrocinio Espigares, Sergio Ros-Montoya and Paul Palmqvist, from the University of Malaga and Joan Madurell-Malapeira, from the Catalan Institute of Palaeontology.